Welcome! Research in the Markant Lab examines interactions between learning, memory, and decision making.

How do people take action to navigate uncertain or changing environments?

How do learners monitor and control their own learning experience?

How do learning and memory influence the tendency to take risks or explore new behaviors?

We use behavioral experiments and computational modeling to investigate cognitive mechanisms involved in effective learning and decision making.

In addition to basic research in cognitive science, the lab explores implications of these processes for learning and decision making in other contexts, including real-world instructional environments and among populations of learners with diverse cognitive abilities.

Learn more about our research by reading the posts below or by browsing our list of publications.

The Markant Lab is part of the Department of Psychological Science at UNC Charlotte.

We operate a shared space and engage in collaborative research and mentorship with the lab of Dr. Alexia Galati.

We actively contribute to academic programs in health psychology,

cognitive science, and computer science.

If you are a student who is interested in the lab's research, see how you can get involved.

17 Nov 2018

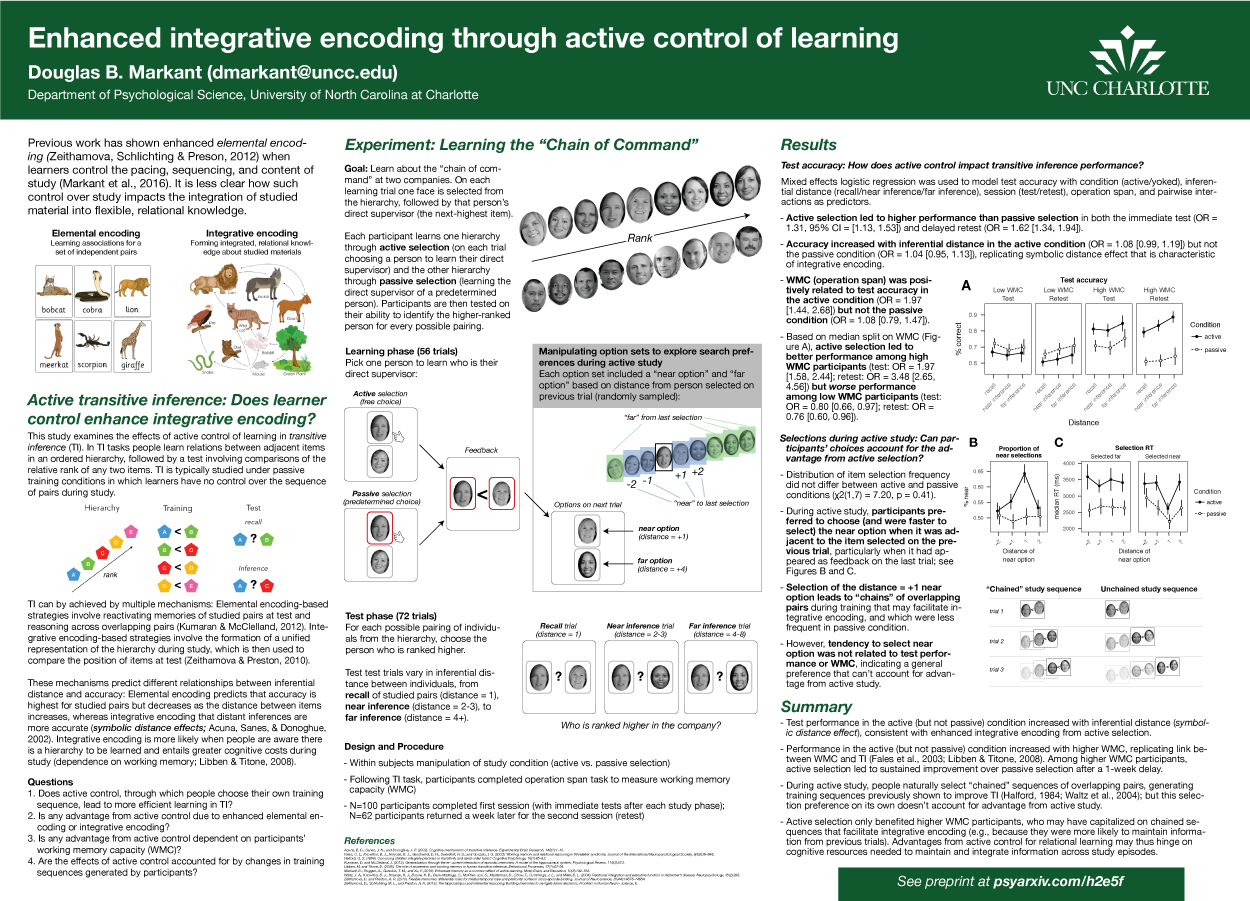

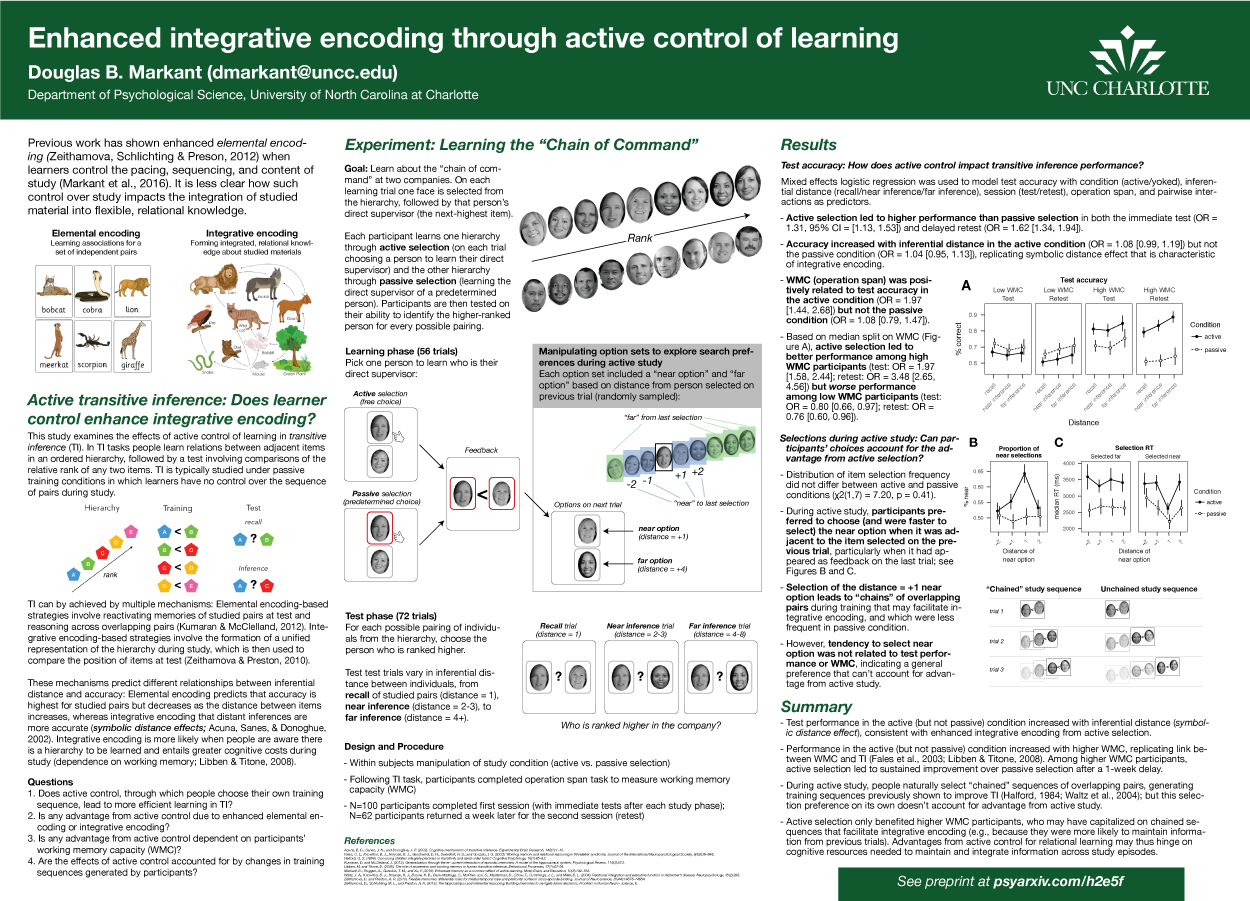

In some prior work, my colleagues and I have found that active control—being able to dictate the content or pacing of information—leads to enhanced episodic memory for materials experienced during study. Let’s say that I’m your instructor and I have a set of definitions on flashcards that I want you to learn. If I give you (the student) more control over the selection and pacing of flashcards, it’s likely that you’ll have better memory later on compared to conditions where you don’t have control.

But as an instructor, I don’t just want my students to memorize a set of independent definitions. I also want them to integrate those concepts together to form some coherent knowledge about the domain. For example, I don’t just want my research methods students to be able to define different types of validity; I also want them to be able to relate them to each other and the broader goals of experimental methods. In contrast to the first goal of forming memories of independent sets of items, it is less clear to what extent having control over learning leads to enhanced integration of study experiences into conceptual knowledge.

The project described in this poster aims to understand the effects of active control on relational knowledge formation. It uses a common relational reasoning task (transitive inference) to disentangle enhancements to memory for individual items from enhanced integrative encoding. The results so far suggest that having control over the selection of items leads to improved integrative encoding over a passive condition lacking such control. Critically, however, the benefit of active control only appears among people with higher working memory capacity. This provides another piece of evidence that the benefits of “active learning” may not be so universal, but instead depend on students having the cognitive resources to maintain and integrate disparate study experiences.

Click on the image below to get the PDF of the poster:

15 Nov 2016

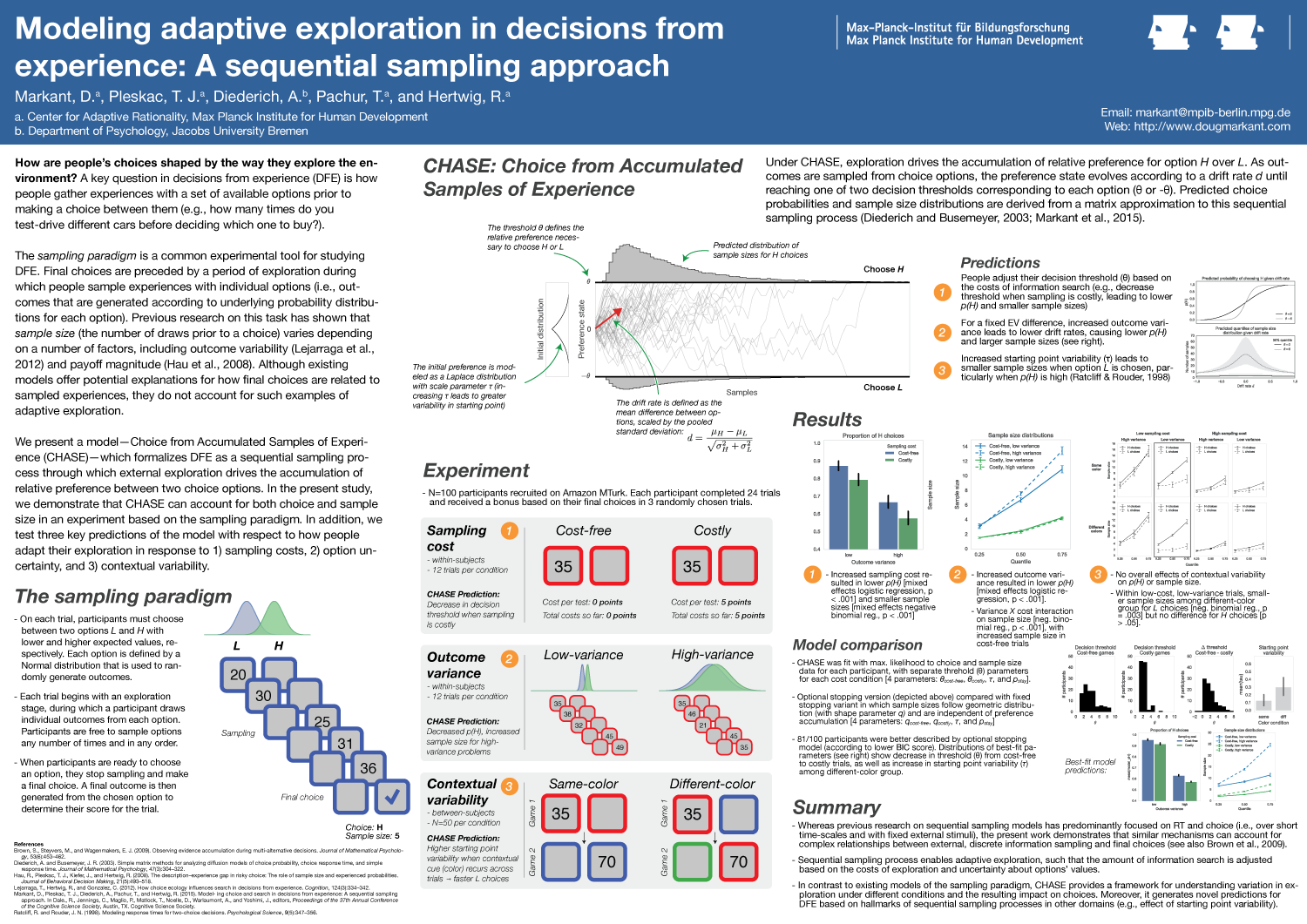

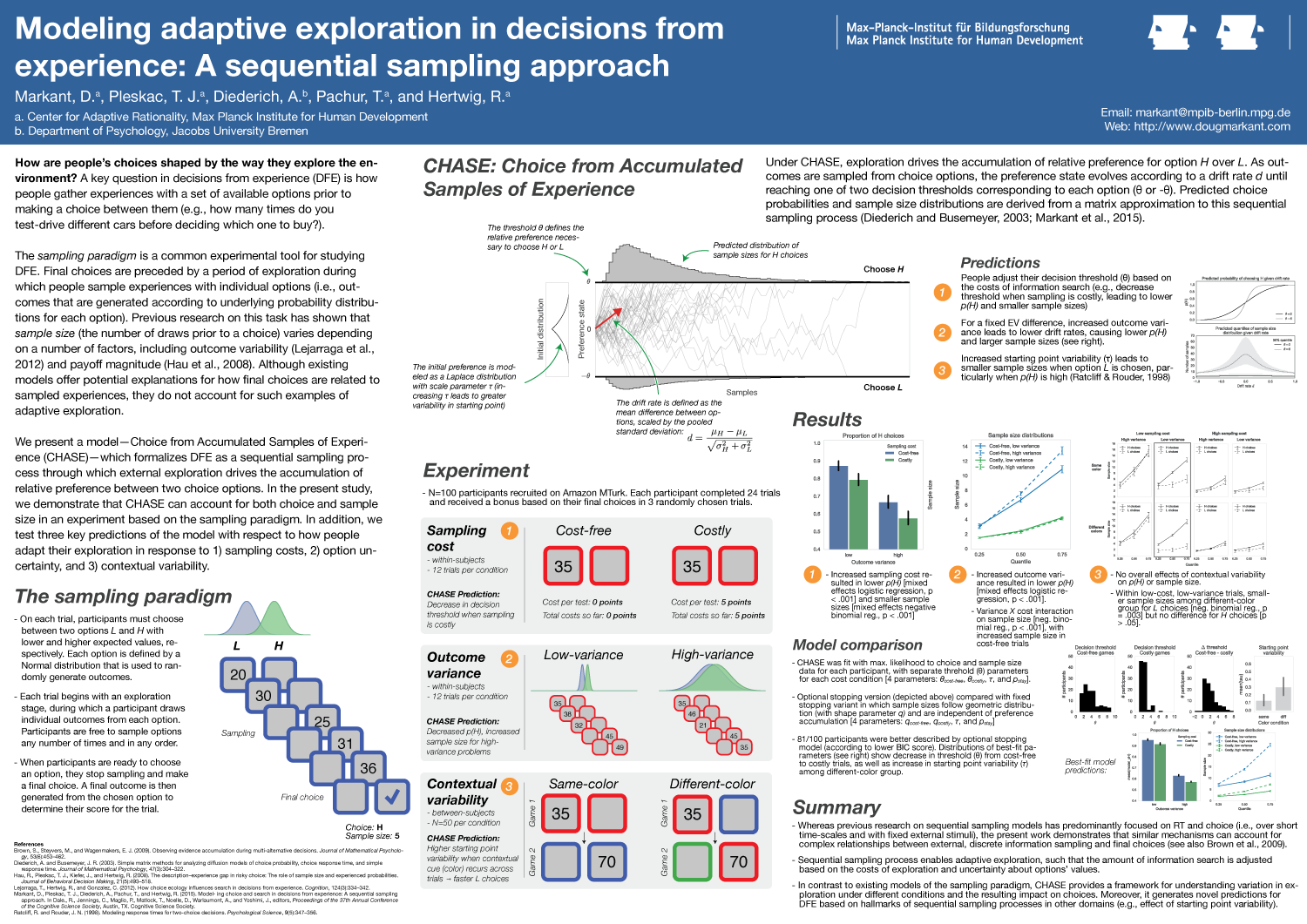

Imagine that you’re on Amazon trying to decide which of two products to purchase. One way to learn about the options before you buy is to look at reviews from other people who have bought the same items. Each review gives you a glimpse into the relative value of each option, and you can explore each item (i.e., keep on reading reviews) for as long as you like until you feel ready to hit the buy button.

So, how many reviews do you decide to read for each product? How does the variability in the ratings affect how long you explore—for example, is there a difference between seeing a string of solid 4-star reviews as opposed to a mixture of 5-star and 3-star reviews? How does your exploration change when searching for a relatively mundane product like a power adapter as opposed to a major purchase like a computer?

At Psychonomics this week I’m presenting some new results from a project where we try to understand how people adapt their exploration in response to these kinds of environmental factors, including the variability in the outcomes they experience and the rewards that are at stake. The experiment described in the poster below was designed to test the predictions of a sequential sampling model that accounts for this adaptive exploration and its effects on how people make choices. Sequential sampling models are widely used to model the relationship between choices and response times in a number of decision making tasks, and our results suggest that similar mechanisms can account for the way that people sample experiences from the environment prior to making a choice.

Click on the image below to get the PDF of the poster:

16 Aug 2016

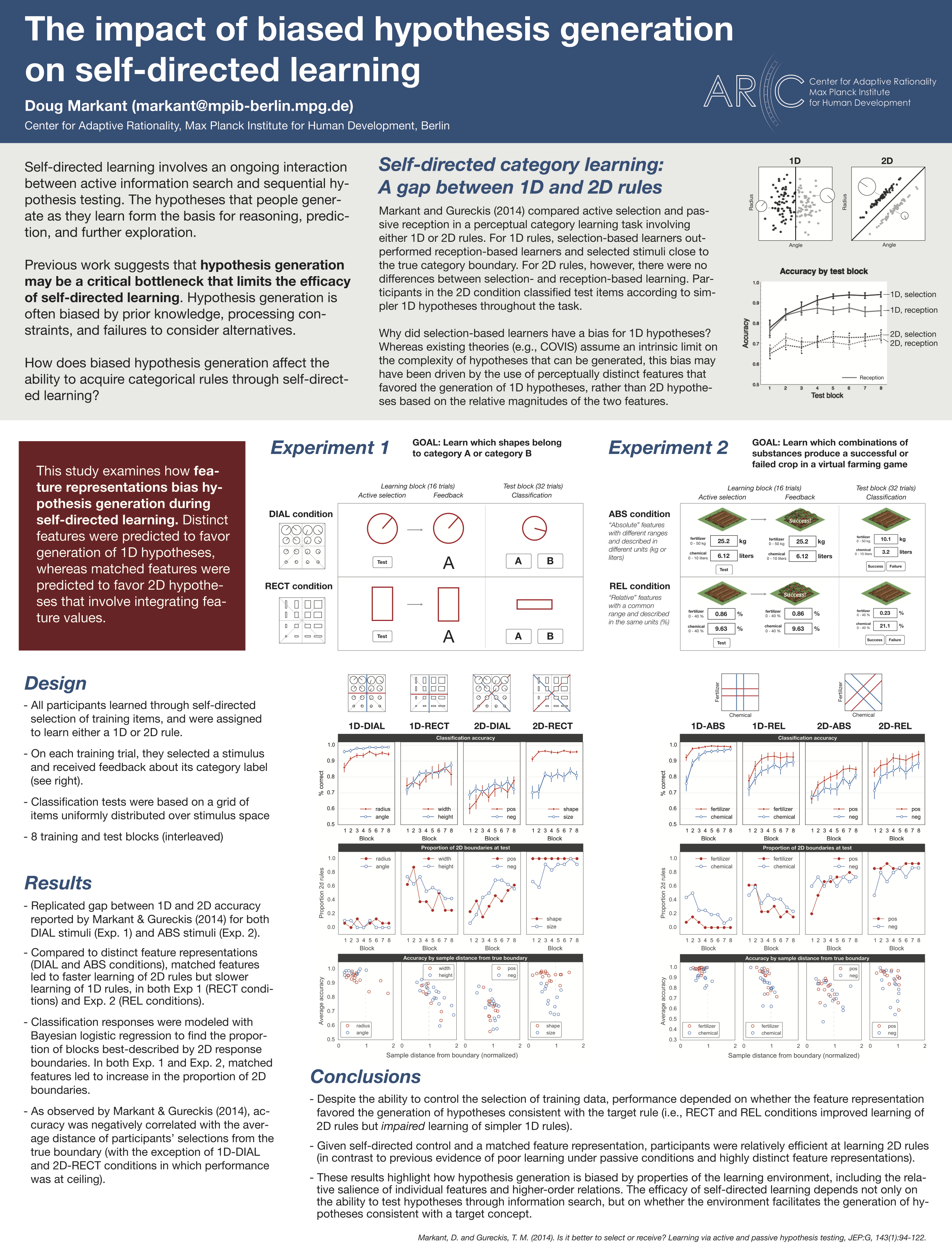

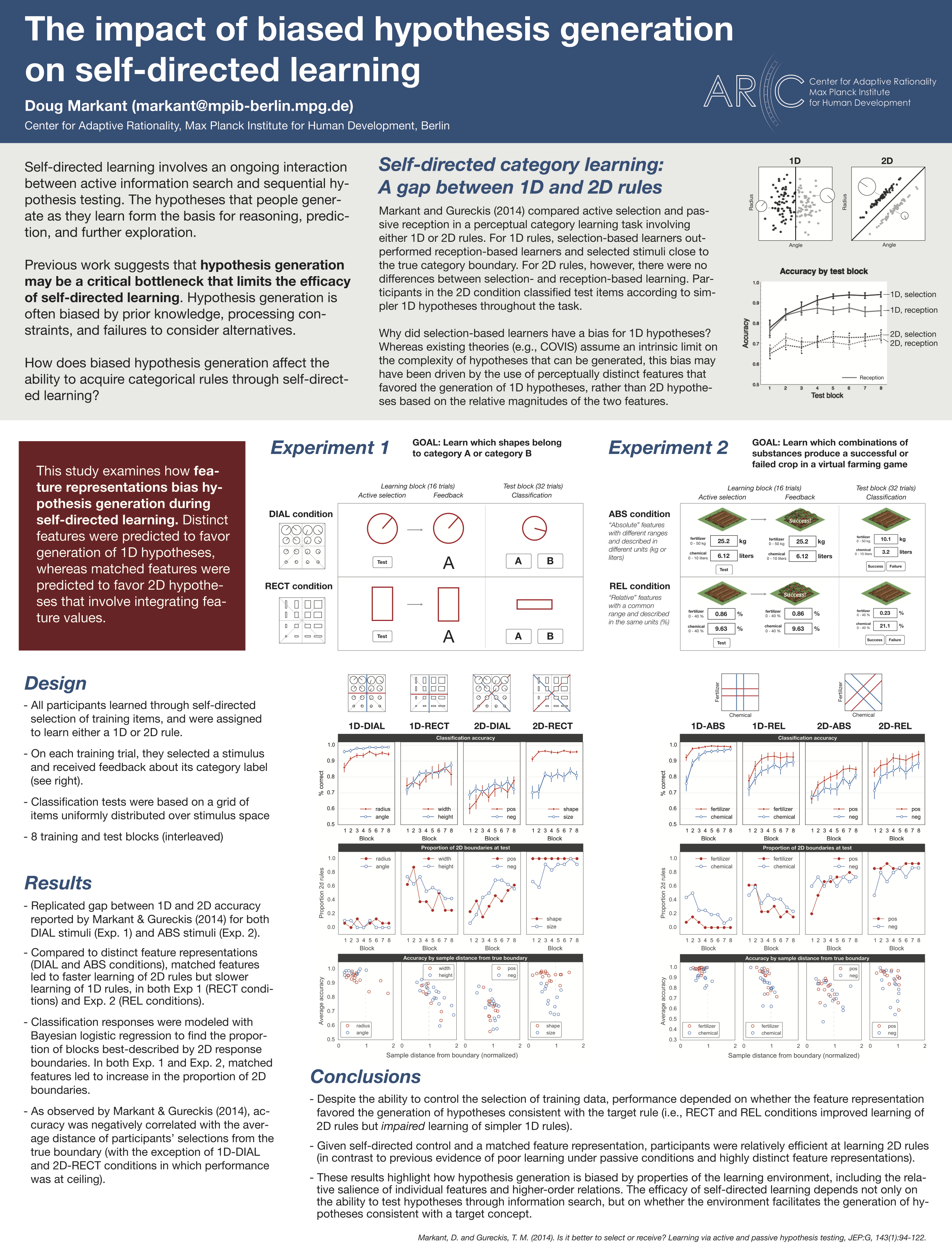

At CogSci this year I presented some new work on hypothesis generation and its role in self-directed learning (specifically, the learning of categorical rules). This project explores the idea that hypothesis generation is a bottleneck in active learning, as is suggested by a lot of work in classic cognitive tasks as well as studies from educational psychology. The results give an example of how biases in the hypothesis generation process can have a big impact on whether people can efficiently learn different kinds of rules.

For more on this project, see the paper in the proceedings and the poster below (PDF).

13 Jul 2016

I have a new paper out in Mind, Brain, and Education, coauthored with Azzu Ruggeri, Todd Gureckis, and Fei Xu. In the paper we argue that one reason active learning improves outcomes relative to passive conditions (like lectures) is that exercising control leads to enhanced memory (in particular, episodic memory for the events experienced during learning).

In many lab-based tasks, having control over learning (e.g., controlling the selection or pacing of new information) often leads to better memory compared to yoked conditions in which such control is absent but the same information is experienced. By surveying a range of research that has employed this kind of active/yoked design in different domains, we outline how improved memory can arise from a number of different mechanisms depending on the kind of control afforded to the active learner. Thinking about real-world learning activities in terms of this basic dimension of control (which is just one part of what people typically think of as “active learning”) may help us understand when and why active learning tends to produce better outcomes than traditional instruction.

A couple of things struck me while researching the paper:

-

Some form of episodic memory is important to many theories of conceptual learning or semantic memory – but episodic memory is not really a focus in educational research. Perhaps unsurprisingly, educational psychologists seem to be primarily interested in measures of conceptual learning: does the student remember the definition of a term, or how to solve a certain kind of physics problem? As far as I can tell there isn’t much work examining memory for the details of the learning experience (e.g., the activities completed, example problems that were encountered, conversations during class, etc.) and how it relates to other performance measures.

-

There’s a similar gap in lab-based research related to inquiry-based learning (including work on category and causal learning which usually shows an advantage for active control over yoked observation). This work has largely focused on the value of the information that active learners select (e.g., do they ask questions that are useful? Can they come up with experiments that lead to unconfounded evidence?). But it seems likely that the same set of memory-based mechanisms could play a role, particularly in real-world inquiry learning settings that involve richer materials and forms of interaction than the typical lab-based experiment.

Writing the paper helped me pinpoint some of these big open questions about how memory and control interact during learning. Of course, despite our best efforts it’s inevitable that we missed some existing work that would be useful. If you know of something relevant or have any other comments about the paper, let me know!

04 Jul 2016

Next month I’ll be participating in a full-day workshop at CogSci,

entitled “Active learning: Cognitive development, education, and

computational models.”

The workshop will feature lots of terrific researchers from the CogSci community

who have been thinking about active learning from many angles.

Come by if you are in Philly on Wednesday!